Anthony Kiendl: Tell me about your installation Chocolate Fountain (2005) and what relation it has to Historic Building (2007), made for the Informal Architectures exhibition.

William Pope.L: Chocolate Fountain came out of my interest in animating architecture and ritualistic images in horror movies. One important visual conceit for me appears in The Amityville Horror. In the film, the home of the central character oozes a black material that eventually takes over the entire building. You have this thing—a building or home— that is taken as very bounded but an event occurs that expands such structures beyond their conventional frame. The same result occurs in Evil Dead 2. One of the central characters, from the exterior, is a small cabin. However, upon entering it, the visitor discovers infinite space; room after room after room. It's interesting that, in cinema, you have this planar structure, a two-dimensional screen that, with the addition of projected light, presents a three-dimensional conundrum with architecture.

AK: Has anything moved on in this work from Chocolate Fountain?

WPL: Yes, in the sense that I couldn't make this piece in Britain: Chocolate Fountain was very site-specific and Britain has a different environmental colour palette. Chocolate Fountain was sutured into another work that tied the first floor of the gallery space to the second. In this building there was an atrium, approximately three metres square. On the first floor it was just a hole; on the second it became a glass-enclosed structure. No one knew its function. We built a platform within the atrium with legs extending down to the ground. I did a performance in the space; dressed as an orange yeti and wrote down from memory Wittgenstein's text "Remarks on Colour" interspersed with recollections of a phone conversation with my brother, Frank, concerning his philosophy on power, women and futility. I designed the performance platform to architecturally communicate with the wall of Chocolate Fountain — as a backstage area. The idea of what is inside something is always interesting to me.

AK: Can you tell me about the inside of the structure (Historic Building) and how it functions?

WPL: Buildings are 'masks', or 'head spaces'. When you are in the presence of a building, you're in the presence of a result of group intelligence. I am interested in the idea of the building as a representation of group mentality and about the way it represents head space. This so-called head space is very 'chunky' and diverse. No matter how sleek and modern a building may seem it is not a single entity but rather a conglomeration of many: ambient, cultural, sculptural and a conflation between the building and its 'mask.'

AK: It's interesting that the work implies that something is happening inside but, as the door is locked, we won't know what.

WPL: Well there's a key in the door. It doesn't work but can be removed (although it won't turn the knob).

AK: I am also interested in the materials: the foam oozing from the edges, the Typar peeling and particularly the choice of the Hudson's Bay blanket. Can you tell me about any of those aspects?

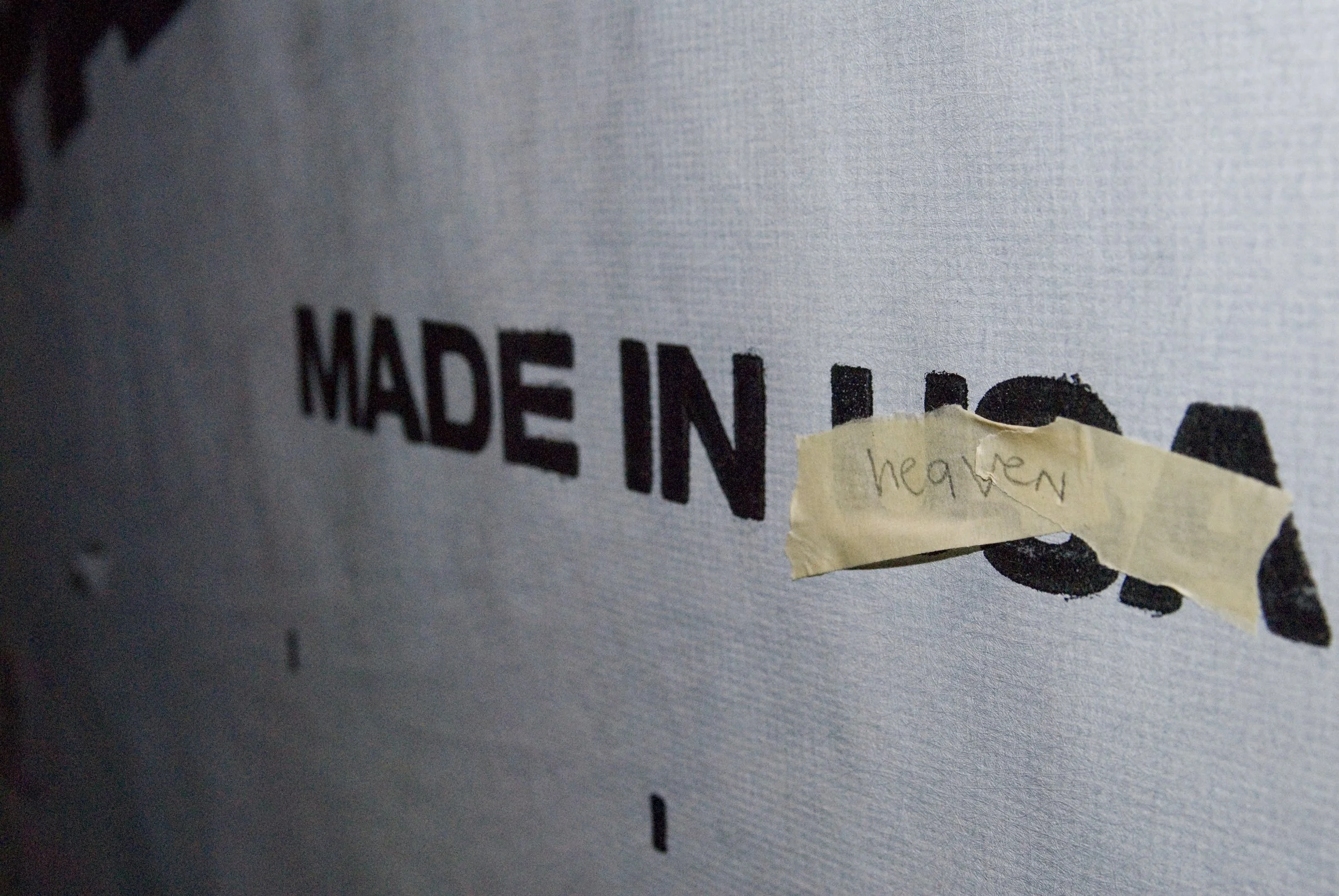

WPL: Again it's a sort of conglomerate/agglomerate or conflation/chunky notion. There are time-honoured notions concerning what buildings can be and what purpose they really serve. Buildings are supposed to be non-sentient, however, there is a long history of suspected sentience in them. They are meant to be reliable, sheltering, a known quantity; but this is simply wish-fulfillment. As such, buildings are sites for negotiating conflict and power. You lock in your logo or stamp on the built environment. In Historic Building you have the residue, the hairy palimpsest of a Hudson's Bay blanket, glued onto the building then carefully peeled off. I did not know that the blanket hails from trade between Europeans and Aboriginal people many years ago. (Often they carried diseases —both intentionally and not—and the latter people had no immunity against them and died). I wanted to layer this sense of European expansionism—slathered with post and lintel construction—with the prefab time of leisure and associations with death. Its all agglomerate-type thinking; perceiving buildings not only as spaces to house bodies, but also as arenas to let loose ideas, or spirits. I think this is where the agglomerate reflects a structure that is not just what you can see, but what you can feel, think or imagine.

AK: In the way that a plain white wall might represent Western, white modernity, the Hudson's Bay blanket is another kind of reading or portrait of the white impact on Aboriginal cultures. I was thinking of your series of Skin Set drawings that are multiple descriptions— this works in a similar way with different identities within this structure; like the chocolate oozing out, impossible to contain. I was curious about the paint on this side because the choice of colour in your other work is very loaded. Does it carry through into this piece as well?

WPL: My colour choices are dictated by conventions of contemporary public landscape and its representation in the media, urban/suburban biospheres and contemporary interior decor. Chance also played a role in my colour choices. Before arriving at Banff, I decided I would limit my pallet to whatever paints happened to be in the gallery's storage. I wanted the process of 'working" the building to be composed of a mix of circumstance, convention, planning and history. In any case, to be at Banff is to be in nature, and so the particular landscape I painted on the building has some sketchy stereotypical relation to mountains, hills, trees and animals.

AK: And the audio again plays into that idea of landscape.

WPL: Also the idea of animation: people animate buildings not only with their bodies but with their use of such spaces. In certain African ritual, there are masks that are never used; they are sacred and not to be worn. So I made this thing that looks like a building, but I allow no one to enter it because I don't want it to function in a typical way.

There are things that fill and fascinate via absence or lack. Perhaps architecture should not be 'said'. Perhaps it should embrace more noise and silence.

AK: I was looking at some of your previous writing and your statement "lack is a value worth having." Is there an element of this in Historic Building?

WPL: In almost all of what I do there is a sense of incompleteness that is an important material. It’s not that I don't have intentions or think in terms of frameworks. I think the drama or story, if you will, compels my insistence to both achieve something and to reconcile intentions with circumstances or adventures that I don't intend.

When Kristeva talks about this radical incompleteness that humans live, she is saying we will never be able to come to terms with the arbitrariness of things. Instead of treating this whirling absence as alien, why not construct it as an opportunity for positive disasters that instruct a discomfort, a lack that's worth having.

AK: Relating to some of your previous works— specifically their relationship to social space and how to be in the world —I was looking at how it deals with social space and urban space and, hence, architecture. Is Historic Building the work that most explicitly refers to architecture?

WPL: My relationship to architecture first came through theatre. Theatre has a very strong tradition of building things for 'the scene.' I was in a theatre troupe for many years and one of the projects we created was a fully standing, working rocking chair live on stage in 30 seconds. It took two years to figure out how to do it. The chair had to be made from seemingly nothing, yet everything. Tools and materials had to be available in plain sight on stage. In performance, once the tools and materials were 'discovered', we cut wood, zipped together boards with screw guns, sat in the chair and recited a complex speech. This was accomplished with little to no transitions. Yes, I've been interested in building for a long time, but not necessarily in terms of 'buildings' or even 'construction.’

AK: I’m interested in the social role of the built environment specifically in your work. I’m also interested in consumption and its role in Historic Building, as it clearly exists in your other works such as Eating the Wall Street Journal.

WPL: Consumption, at least for me in this project, is more about what comes out the nether end. When people think of consumption, they think of it mostly as something you take in, when it's also what you 'put out'. When I think of a building, I think of it as a sort of sentience that gives off certain effects. Houses are porous and chambered like a creature with air for organs.

In the Robert Heinlein novel, Stranger in a Strange Land, the hero Michael Valentine is looking at a house. Standing next to Valentine, looking at the same house, is an alien for whom sense impressions are next to godliness. Valentine asks the alien "What do you see?" The alien responds: "A building with two sides." Valentine is puzzled and says: "What do you mean a building with two sides?" The alien responds: "That is what I see: I see a side, and another

side." The alien leaves. A short time later Valentine approaches another character, his lover, and asks her why the alien described the building so strangely. The lover explains that the alien can only express what it can see. Anything else would be a hypothesis.

The front of Historic Building should not reveal the back, nor the left or right sides of the structure; these are things you might only be able to infer. The building unmakes itself as you walk around it. The viewer visualizes it mentally as they physically interact with it.

I guess I am interested in an analytical consumption. I am interested in culture that speaks to us about how we interact with it. In art we crudely suggest such relations at various times. Most of these instances are proffered as intellectual, not communicative, spiritual or even cultural.

Such an example is Robert Morris' Box with the Sound of its Own Making. For me, this piece evokes landscape and issues to do with scale, body-object relationships and what it means to make something. Historically, much has been made of the tautological aspect of the box because it supposedly contains an actual recording of its own making. The conceptual conceit of the work can come off too neat but, for me, it is its scale that provides an added layer of significance. The box is small and suggests the handmade, however, the recording only documents the sound of construction not, for example, the purchase of its constituent materials or the clean up after assembly. The appearance of conceptual elegance was moreimportant to Morris than to me.

I am interested in the social history of plywood, for example; where it comes from, how it's made. I am not afraid to risk visual elegance by making this sort of interest evident in a work. I think we sometimes confuse visual elegance with conceptual rigour. Wittgenstein once said: "What if you make a proof that is so elegant and so precise that it leaves the ground of meaning? What utility can a proof of this sort have?" I was fascinated by Morris' little box because, by turning on itself, it set itself apart as a semi-sentient in a landscape. The box was a performer, it was not about its own making but, rather, its inhabitation.

A version of this text was first published in Informal Architectures: Space and Contemporary Culture, Anthony Kiendl, ed. London: Black Dog Publishing, 2008. It was edited and updated here in 2025. © the authors, and artist, all rights reserved.